Bryan's Song

Fogarty's immense natural talent on the ice was generational, but he may have played a generation too soon.

“When the daylight is falling down into the night

And the sharks try to cut a big piece out of life

It feels alright to go out to catch an outrageous thrill

But it’s more like spinning wheels of fortune

Which never stand still

- Big City Nights – Scorpions

This wasn’t The Forum, nor was it Maple Leaf Gardens. For one, those venerated arenas were enclosed. Eisstadion Mellendorf was open to the elements — there were no exterior walls running the length of the rink. Whatever the temperature was outside, it was inside.

Still though, if you were an ex-National Hockey League player seeking a decent paycheque, it was a great place to play, far from the pressure and scrutiny of the North American game.

The arena held just a few thousand and was home to the newly renamed Hannover Scorpions playing in the newly formed DEL, top-flight German hockey, which was just three years old.

The team was loaded with imports; “les l’enfants terrible” found the town of Wedemark, site of the rink and 20 minutes to the city centre, an ideal homebase for a European vacation.

Why not?

Hannover was sponsored by a beer company and bore the name of the local metal band gone famous — Scorpions. They skated out to start each game to the group’s biggest hit, “Rock You Like a Hurricane.” Nightlife came easy, winning didn’t, at least until they had to start trying.

The head coach saw the 1997-98 season slipping away and needed to make an adjustment, fast. Having just turned 35, Kevin Gaudet was not much older than most of his players, even younger than a few, and his foreign stars marched to their own drummer. So he struck a deal. It was, essentially: win on the weekend, when most of their games were scheduled, and you can do what you want until practice on Wednesday. Letting the horses run free sat well and no one was more excited about the prospect than a 28-year-old newcomer from Brantford, Ontario.

His name was Bryan Fogarty.

He was big and tall with light brown hair, hazel eyes, a raspy voice and a laugh that could only belong to him. You couldn’t forget it, even when the man exhibited the zeal of a little boy at the prospect of being left to his own vices.

Hannover’s bad boys were free to ride, no questions asked and they responded in kind.

They were no longer the team that see-sawed through the opening three months of the season. They were formidable, especially at home, and they made the playoffs for the first time in franchise history.

“After a while, nobody could beat us,” Gaudet remembers. “They’d come into our barn and Fogey would win the game by himself, he wanted to party so bad for two days.”

Gary Leeman remembers it a little differently, but where the former NHL 50-goal scorer and the coach can agree is that the team loved to party and Fogarty never made Tuesday’s daytime skate or evening practice. And none of this mattered when he came to play.

Every so often at the morning skate, while the coach was surveying his herd of players circling the ice. A rogue gust would snap Gaudet out of his focus, a nimble giant had just breezed by flashing a grin, he was just far enough away to be far enough away but so close that just for a fleeting fraction of a second, you could feel his current run through your body. That was No. 43.

Few skated better, even less had his ability. He could carry the puck from behind his own net and break a game open in an instant and when he was on, he did.

Today general manager Eric Haselbacher sits back in his office and recalls his friend with a smokey laugh. They all made up nicknames that season, Leeman was Golden Eye because he could find the net. Jason Lafrenière was The Hawk because of his nose. Fogey was The Mailman, after the NBA star Karl Malone.

“ ‘I deliver the mail!’ ” Haselbacher says in an emphatic impersonation of Bryan.

It wasn’t for his ability to finish scoring plays, though he easily could if he wanted, it was his vision to set them up. He was more like John Stockton, Malone’s point guard with the Utah Jazz.

Many will tell you he was on par with Paul Coffey, they used to say Bobby Orr. After all, Fogey broke Orr’s OHL goal-scoring record for defencemen in junior. But he never once indulged those comparisons, publicly or privately.

Ask about Bryan to anyone who knew him well or those that watched him torch their team on the ice or from a well-worn seat in Sudbury, North Bay or the Soo and you will elicit a subconscious chain reaction: a stunted exhale through pursed lips, exalted praise, then a pause… and you still haven’t gotten to the fans in his home rinks.

Management, coaches, players and fans will tell you he was one-of-a-kind, jaw dropping, unbelievable, breathtaking… the best fuckin’ player they ever saw play.

That is if they respond at all.

“I loved Bryan, I really did,” laments Gaudet, “Everybody did.”

“I had a lot of fun with him and I’d do it all over again,” Leeman says about the lone season he played with Bryan. “He’s missed.”

Haselbacher puts it more succinctly, in his second language

“He was too good for this earth.”

NIAGARA FALLS: 1988-89

“Sometimes I think it’s a shame

When I get feelin’ better when I’m feelin no pain”

-Sundown – Gordon Lightfoot

The red Chrysler LeBaron is a sight to behold as it streaks toward Copps Coliseum in Hamilton. As the April dusk gives way to the dark of night, two young headbangers are up front with the world by the tail, the engine revs as the car motors down the Queen Elizabeth Way highway, youthful exuberance radiates from the interior.

Scott Pearson is riding shotgun. The rugged left wing was mercifully traded from the Kingston Raiders in December. Awaiting him in Niagara Falls was Fogey, his former teammate who had been granted his freedom in the offseason and put in a good word to ensure the same for his old buddy.

Tonight he is at the wheel, in control, like he has been all season.

Fogarty had re-written the record books in his final year of junior, setting marks that seem untouchable three decades later. Pearson had arrived as it was reaching its zenith. His fellow first-round draft pick was averaging 2.75 points per game and threatening long-standing scoring records set by players that would go on to be the greatest in NHL History.

Finally, it seemed that Bryan was at the top of his game.

When he was rising through the ranks in Aurora and in his first seasons of junior with Kingston, Fogarty was a boy in an adult’s body playing against young men. Now he was taking full advantage of his talents.

The late Bill LaForge has been described as older than old school, but also a non-conformist, Eddie Shore meets Roger Neilson — anything but conventional. The veteran coach wasn’t conservative when it came to his star. He unchained Fogey, set him up for success, on a team of thoroughbreds designed to win by filling the net.

A typical forecheck might have one or more of the three forwards pursuing the puck carrier.

Not for Bill.

The 41-Thunder, for example, was designed to unleash hellfire, two forwards would charge deep on the player possessing the puck, another two would go hard low on the boards, clogging the puck side. The lone D would protect the middle of the ice.

It was like playing with the goalie pulled. Usually it was launched if the team was trailing and it resulted in several comebacks.

Howling like coyotes at their coaches' behest, they skated into the offensive zone with conviction, hoping the combination of pressure and intimidation would result in a hurried play and a turnover.

Forced turnovers, in part, allowed Bryan to reap the benefits of innovative offensive schemes which enhanced his generational capabilities as the Thunder charged through the season.

They scored 410 goals and allowed 319. That averages to 6.2 scored per game versus 4.83 against. The Cornwall Royals were the closest team to them in overall scoring, with 60 fewer goals. No team has surpassed that mark since and only Bert Templeton’s 1976-77 St. Catharines Fincups scored more in a 66-game season with 438.

If you weren’t on the ice, you had a good view from an elevated bench, another tactic used by LaForge to make his team more fearsome. Across the ice, the opposition sat low — that was deliberate too. The tops of some helmets were all you could see as they stared down at their skates, puzzled. They should have been. Their blades had been dulled from walking over a mat covered with metal fillings from the skate sharpening machine and some sand for good measure.

This was the art of war. This was firewagon hockey. This was fun.

The coach's son had a front row seat to watch the offensive explosion led by Fogarty.

“I was in awe,” Bil LaForge says, “He was so good that if he took the puck from you, you weren’t getting it back.”

A stick junkie, he remembers the white Louisville TPS with blue lettering as more of a magic wand than a wooden stick. He still has a couple, somewhere.

Bil, like his late father, has turned a love of the game into a career and also shares his dad's name, albeit not the spelling. Today he is the GM of the Western Hockey League’s Seattle Thunderbirds. When he was 14 going on 15, his role with Niagara Falls was an “unofficial scout” and an early video coach.

He would also skate in practice, one time faking a slapper and going around Fogarty, who was surprised but unoffended.

They joked about it for weeks.

Fogey even let him drive the LeBaron around the parking lot before they ripped out onto Kitchener St. to grab some food.

Bryan was a rock star. Brad May thought so.

Before he was a Stanley Cup champion and the focus of Rick Jeanneret’s most famous call as playoff overtime hero for the Buffalo Sabres, he was a rookie in Thunder training camp when Fogarty returned to junior from the Quebec Nordiques. He remembers the convertible with personalized plates bought with NHL signing bonus money pulling into the parking lot.

Bryan personified the big time. And lived like it too.

May and Keith Primeau rented an upstairs apartment above an elderly couple not far from the rink on Peer Lane.

All three attended Stamford Collegiate on Drummond St., a five-minute drive from where they played. At lunch, after Fogarty’s two morning classes, he would let them take his wheels and they’d drive him back to their apartment. Bryan would sleep off the previous night, while they headed back to school in his ride. When the final bell rang, they would pick up Bryan before racing to Centre Street for practice. The mist from the Falls rising in the distance.

“He had it all,” May says. “The coolest car, the girl, the money, the career.”

Stan Drulia had returned to the OHL as an 20-year-old overage player after tallying 121 points the season prior. His numbers were about to get a further boost with the new addition on the backend.

“I wouldn’t have had the year I had without Bryan Fogarty,” he said. “He could cut on a dime through a small hole and find you through traffic. His ability to shift weight was so subtle and the way he could change gears and go east-west was off the charts.”

Drulia set the all-time OHL points record that season in addition to winning league honours as the top-scoring right wing and overage player. His 145 points would have easily carried the scoring crown in most seasons but he missed 19 games, and wound up 10 behind Fogarty.

The elder LaForge told Patrick Kennedy of the Kingston Whig-Standard that he liked his players to play with pride and a lot of self-esteem. That worked for Bryan.

On Remembrance Day, he scored three goals and assisted on five in an 11-2 win against the Sudbury Wolves.

To this day, when the Wolves score, a howl goes out over the PA at the Sudbury Community Arena, then a taxidermied wolf passes over the ice along a wire. May and his teammates laughed on the bench thinking about the workout it would have got if Fogarty was playing for the home team. The still standing franchise record snuck up on them because of the season Fogey was having.

“It gives me chills remembering that game,” May says en route to Arizona from his winter home in Laguna Beach, California. “He was already scoring three or four points a game, but that night he had four or five and then it became six, seven and eight.”

Bryan did it again on Jan. 12, scoring twice and setting up six against the North Bay Centennials, once again leaving the far reaches of the OHL universe after another eight-point game.

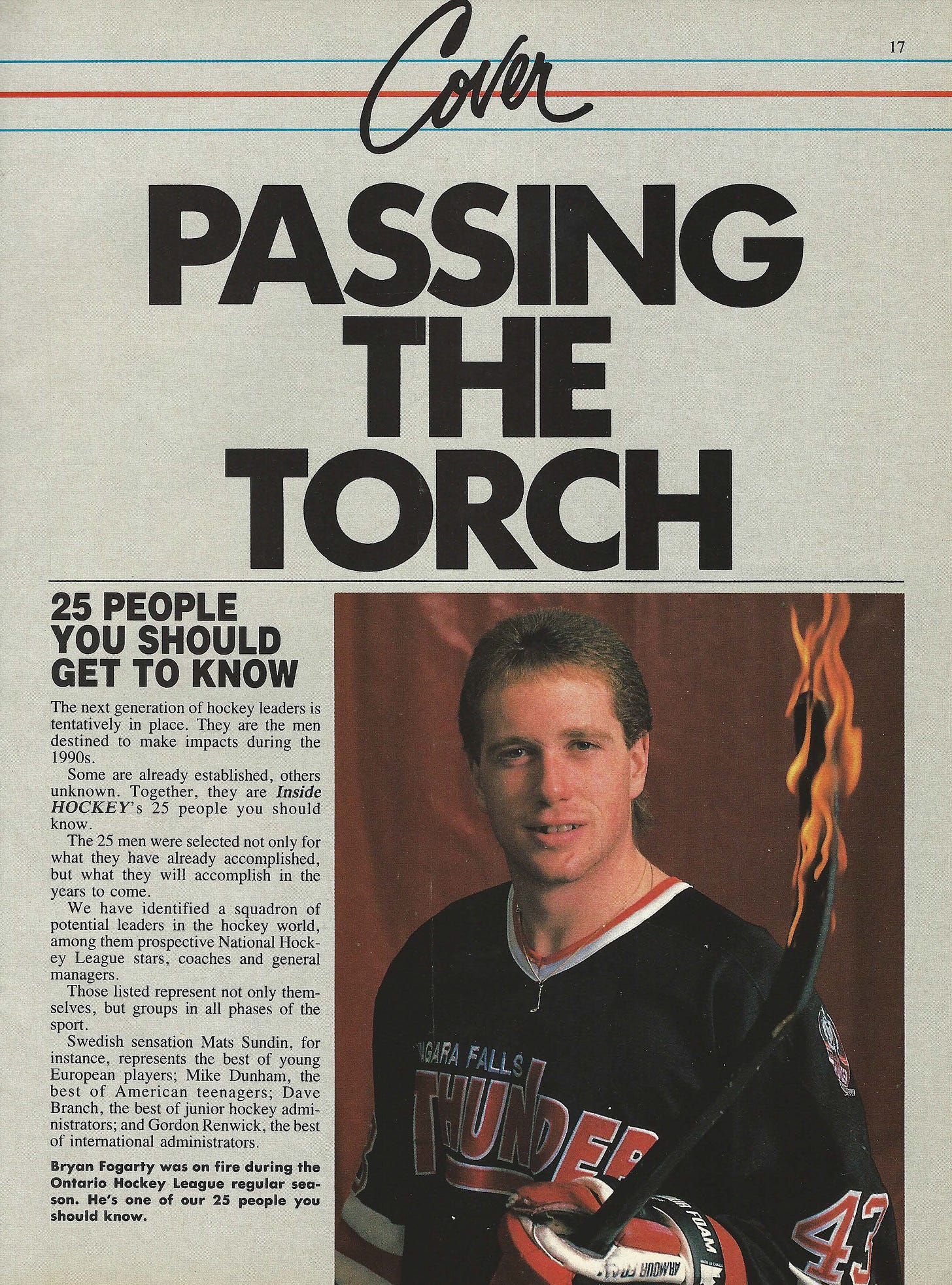

Quite simply, he lit the league on fire, prompting a cover story in The Hockey News publication Inside Hockey where he posed with his stick pointed toward the camera, flames engulfing the blade.

“He got points like a first-line centreman would get.” Pearson recalls from his home in Atlanta. “Bill let him be Bryan, whether that was good or bad, he let him play and didn’t hold him back at all. He could kind of do what he wanted on and off the ice for that matter and I think Bryan appreciated that and respected that and he came to play.”

He was barreling through the opposition with the aid of a sports psychologist, Dr. Max Offenberger.

A mental skills coach was a foreign concept in junior hockey and could be filed under New-Age, Self-Help at the NHL level.

But LaForge had engaged Offenberger for years, since he was coaching in the Western Hockey League. He welcomed the tall, slim gentleman into the room of teenaged players and walked out, allowing the doctor to introduce himself.

Whatever was going to be said between a player and Offenberger was like confession, trust would never be broken.

Your billets are pissing you off?

You’re worried that you might have knocked up your girlfriend?

Maxie, as the team called him, was there to listen. When he visited the team, he had a hall pass, allowing him to move freely through the inner sanctums of the dressing room and bus.

He was upbeat and positive with a “larger than life” attitude, a sharp deviation from the direct and often harsh interactions of that world.

“Max had a unique connection with Bryan,” Pearson said. “Bryan was able to talk openly to him about a lot of things and he helped free Bryan of those things. He truly helped him get everything together.”

What those things were? That wouldn’t be known until it was too late.

Fogarty’s stats seemed to compound. Twenty-seven points in his first 10 games. He got his 95th point in his 30th game. By February, he had accumulated at least one point in 40 of 44 games, most nights more.

On Feb. 2 he was on the precipice of history at home against the London Knights. He was one goal away from tying Bobby Orr and Al MacInnis’s OHL record of 38 in a season by a defenseman and three points away from tying Denis Potvin’s mark of 123 points by a blueliner.

When the final whistle blew, he had scored twice and set up four in a 7-2 win. Mission accomplished.

Mark Zwolinski of the Toronto Star wrote that Fogarty’s record-tying goal “dazzled onlookers.”

“Fogarty was knocked to his knees in a praying position but managed a shot that found a corner of the net behind (Peter) Ing.”

“I didn’t even know it went in,” he said “The last thing I remember, I was knocked down...I put my head up and saw the puck on the ice in front of me. I took a swipe at it and it went in.”

No big deal. He was glad the “nerve wracking” chase was over.

It was standing room only that night at the Niagara Falls Memorial Arena and fans and teammates flooded the ice for both goals.

By the end of the month he completed the offensive-defenceman trifecta when he surpassed Doug Crossman’s record of 96 assists.

Brian Kilrea had seen a thing or two in 14 years as a career junior coach with the Ottawa 67’s. The two-time Memorial Cup champion was clear on what the hockey world was witnessing, this kid was no Denis Potvin.

Bryan had “changed the game like Orr and Coffey did,” he told Dave Hall of the Windsor Star.

About three-and-a-half kilometres from the rink, not far from where the tourists watch the Falls plummet and crash into the basin, is a neighbourhood called Silvertown which overlooks the Niagara River as it veers sharply, up and onward out into Lake Ontario.

Bryan lived on Ferguson Street.

Close to where the water bends is another attraction, the Niagara Whirlpool. Created by powerful conflicting currents, at times its loud enough that residents can hear it from their front porch, the rapid rotations that can draw you in and take you down.

LaForge was looking for a good place to keep his talented yet troubled star in line. Steve Ludzik suggested a unit owned by Mrs. Norma Mundy.

Ludzik’s NHL career was winding down as Fogarty's entrance into hockey’s top flight was ramping up. Their lives intersected for the first time during Bryan’s electric 1988-89 season. Hockey circles, like all circles, are small. Ludzik, who starred with the Niagara Falls Flyers a decade earlier, was making his permanent home in the city.

Later they would meet again in Detroit, when it was different, not like now, where Bryan was on top of the world.

It was the first time in his blossoming career that he was truly one of the older guys, and he was treated like it, set free on the ice and given more leeway as a man.

If his landlady peeked through the curtains and saw him coming home as the sun came up, noticing he smelled like booze and cigarettes after a night at the Bon-Villa or sauntering in from Bedrocks across the bridge in New York state... so what? It was better than driving straight back to Brantford in the same condition.

Even after going hard all night, In practice and on game days Fogarty had it.

When Bryan was leading the breakout drill, Drulia recalls being told to skate up the middle and he would get the puck.

“What are you gonna do?” Drulia asked?

“I’ll figure it out when I get there.” Fogey smirked.

“He floated,” Ludzik recalls now from his home in Niagara-on-the-Lake, “It was like his skates barely touched the ice.”

He was the alpha, a good cut above six feet and 200 pounds. He was brawny, yet nimble. Fogarty could exert his will by force and form.

“Game in and game out, you knew that he was a threat at any point.” Pearson said. “He just did things that a lot of players would only dream of being able to try and do and he did them effortlessly.”

It was almost surreal that he was there to begin with.

Fogarty had been selected ninth overall by the Quebec Nordiques in 1987 NHL draft, ahead of future teammate and Hockey Hall of Famer Joe Sakic. In the lead-up to the big day, he was questioned about his partying ways while playing for the Kingston Canadians. It irked him, but Nords GM Maurice Filion had faith in the kid he just picked.

“I think people enjoy building things up like that,” Filion told the Whig-Standard. “They’ll say he had a lot of problems off the ice. You take some of the things and let some go. I don’t think it’s that bad.”

The night before her son was called to the podium at Joe Louis Arena, Virginia Fogarty won $905 at bingo across the river in Windsor. The future was bright.

While he had not made the big club out of two training camps, the Nordiques were encouraged by their gamble, even if their dynamic blue-chip prospect didn’t attend Canada’s training camp for the world junior hockey championship.

He wanted to reduce distractions and focus on the Thunder.

Truth be told, the world juniors brought the focus of Canadian media outlets. He would face questions about drinking, stemming from the summer of 1987 when he had been kicked off the national junior team after a hotel room was trashed by a firehose after a party.

“He plays like Paul Coffey,” Pierre Gauthier, Nordiques director of recruiting, said of Fogarty mid-season. “We took a risk (drafting him) but we have no regrets at all.”

So yeah, he was sure as hell gonna stay where he felt most comfortable because for the most part, he had left all that noise behind in August when he was dealt.

“Bryan was a quiet guy, he didn’t like publicity,” Drulia recalls. “Being at the rink, on the ice is safe, you’re not thinking. He was happy there when no one was poking and prodding.”

“Coach” as Drulia still calls the late Bill LaForge Sr. was firm yet flexible. He could work the team into exhaustion in off-ice training, or have them run full force into each other behind the net in equipment, yet treat them like adults.

His friendship with the family was built to last, wherever he was in the world, Bryan knew if he called, his old coach would answer the phone.

“My dad always loved his players,” LaForge says. “They knew he cared about them, Bryan knew he cared about Bryan ‘the person’ first.”

In early November the Thunder rolled through Kingston, Fogarty fell without being touched on his first shift and committed a brutal turnover, then to the great misfortune of his old team, settled down. He assisted on the opening goal of the game and scored twice in a 6-2 win against his former team. 2 and 1, just another walk in the park. LaForge marveled while Fogey’s first junior coach looked on amongst the crowd.

Fred O’Donnell watched Fogarty become the player he always thought he could be, the player everyone was expecting to see.

“I knew what he could do and he didn’t disappoint,” O’Donnell remembers. “You could see the upside with Bryan very quickly…we had him pretty young.”

The Niagara Falls Thunder’s inaugural season was the best of the eight they played in the border city before moving to Erie, Pa., in 1996.

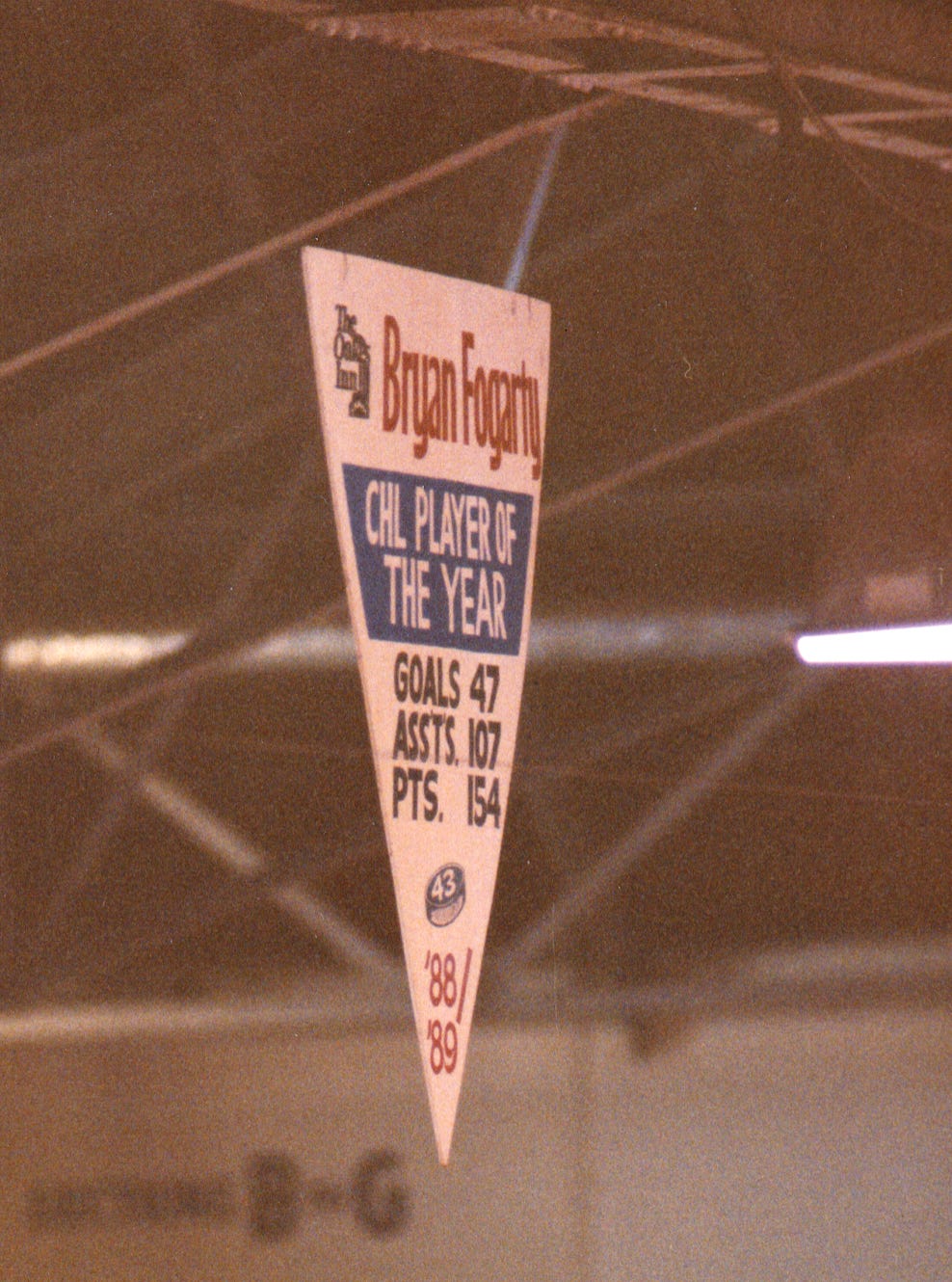

Fueled by Fogarty, they went to the league final before losing to the Peterborough Petes in six games. He led the league with 155 points (47 goals, 108 assists), surpassing Cam Plante and setting the CHL record for defenceman, which has remained his ever since.

He swept the year-end awards including the Canadian Hockey League player and defenceman of the year. One of the trophies came with two tickets to Hawaii.

At the banquet, he walked over to LaForge and whispered. “How did you know I was capable of this?” LaForge replied emphatically, “Because you, have, it.”

Bryan insisted his coach take the tickets but Bill refused.

“When you make it to the NHL, and you can afford it, we will go to Hawaii together.”

Fogarty’s OHL marks for goals, assists and points still stand. He is the lone defenceman to ever lead the league in scoring. The closest any player has come is Ryan Ellis, who tied for fourth place in 2010-11 with 101 points. The high-mark of eight points in a game was equaled once, in 2003 by André Benoit.

There is a picture of Bryan from that year that captures him at an optimal moment during that sensational season. He’s looking downward and you can sense he is happy and relaxed, his mouth flashing a toothy grin like he is about to laugh or just had a good one with a teammate.

He is 19. It doesn't get better than this. It never will.

Pros will tell you that the friends you make in junior are not the same as those you make in the show. There is a purity in the chase, untainted by mortgages, wives, kids and the other serious matters of living as a true adult.

“You’ve got a time in your life together that was special,” Pearson said. “ You’ve got a bond.”

So for now, two friends who endured the frustration of playing for a bad team in Kingston, could let loose tonight by getting up to no good. Scorpions albums’ Blackout and Love at First Sting blast from the tape deck, Metallica awaits about an hour down the road on the Damaged Justice Tour, way less than that at the speed they were clocking.

A red LeBaron races into the night

KINGSTON: 1985-86

Most major junior teams in Ontario nowadays play in scale models of NHL arenas, with a bowl of 5,000 to 6,000 padded seats, suites, and a four-sided video scoreboard above centre ice.

In Fogarty’s day, going to an OHL game typically meant entering a barn built just after the Second World War. They each had their quirks, inside and out but only in Kingston was there a horse track next to the rink.

A new coach looking to create structure can always start with some come-to-Jesus conditioning. There was no better place to get the players into shape than the oval where ponies were put through their paces.

In the spring of 1985, Fred O’Donnell was hired to coach a team that his predecessor once said was simply “in disarray.”

The writing was on the wall for Rick Cornacchia from the outset. He saw no discipline and sought order. The curfew he set was broken on the first night, after a season-and-a-half, he was fired.

They had failed to make the playoffs for three consecutive seasons, which is a cardinal sin in junior hockey. It was the lowest point in the short history of the franchise that a group of local businessmen had bought and moved from Montreal to Kingston in 1973. The Montreal tricolour and an anglicized version of the name stuck, but the greatness vanished.

The Canadians were bad, but in junior hockey, where players are 16 to 20 years old with a finite tenure, there is always reason for optimism when you can start anew through the draft every three or four years.

A handful of the hopefuls running around the track were part of a bumper crop selected by general manager Ken Slater. However, their top pick was not leading the way in physical fitness.

Bryan was selected first overall by Kingston in the 1985 OHL priority selection draft, but he was not the Canadians’ first, or even second choice.

Adam Graves had informed the team that he would only play for the Windsor Spitfires or Kitchener Rangers. Ken McRae made demands through his agent that could not be met, so a new coach and soon-to-be departing GM toiled through the night and went with the Fogarty kid who the scouts loved.

On draft day, Bill Smith, the chief scout for the Aurora Tigers, Bryan’s Junior A club, told the Whig-Standard, they had gotten themselves a hell of a player.

“There were seven teams that expressed interest in him in the first round and it’s sort of fitting that he was taken first because he is the player with the best potential in the draft.”

“I like to play an offensive, physical type of game,” Fogarty said. “I like to play the puck.

“I had a good year last year. I didn't stand out, but being four years younger than most of the guys had something to do with that.”

Slater saw a future world junior team player who would definitely make the NHL with his pinpoint left-handed shot, and million-dollar wheels.

The sage career scout reinforced his reputation as a strong evaluator of talent on that day in June at the North York Centennial Arena. After Fogey, Slater took Scott Pearson in the second round and Steve Seftel in the third. Mike Fiset was selected in the seventh and then they took a flier on Jeff Sirrka in the 17th round.

Ken Slater had restocked the stable for a cycle of potential success, but he wouldn’t be around to see it. Before the season, he was hired as a scout by the Vancouver Canucks. O’Donnell would assume GM duties, thankfully the cupboards were full and the bright light of the future shone through Fogarty, their 16-year-old dynamo on the backend.

“He was ready to play when he got to us, no question,” O'Donnell said. “He was the most talented player I had ever coached, he had great hockey IQ and unique mobility in that he had no weakness.”

O’Donnell won't tell you that through the 1970s and early 80s, he restored the Queen’s University men’s hockey program to respectability, or that he was named Ontario university coach of the year and guided the Golden Gaels to their first provincial title since the year that the First World War began. He doesn’t mention that coaching university hockey was a part-time position, he will only say that he left to pursue a full-time opportunity.

O’Donnell also will not tell you that after being thrust into the dual role of coach and GM he steered the Canadians back to the playoffs in his first two seasons and was named coach on the league’s third all-star team for 1986-87. Nor will he give oxygen to the notion that an ownership mess led to his departure, amid published reports of them wanting him to relinquish his management duties. He just moved on to selling real estate.

And so Fred O’Donnell most certainly isn’t going to share the sensitive details of Bryan Fogarty’s missteps in Kingston.

Expecting a call about his oft-remembered defenceman, O’Donnell is wise, clear and careful. In his soft cautious tone he could tell you a lot more than he will.

Bryan’s travails, which surfaced nationally when he turned pro, have caused many who cared about him to go through a painful exercise when talking about him. The prevailing sense is that it’s much harder for someone that was tasked, so early in his life, with keeping him from going wayward.

Now 71 and recently retired from nearly 30-years in real estate, Fred, expecting a call, volunteers that he wrote a few things down in order to jog his memory.

Twenty seconds later, he had recited an uninterrupted comprehensive scouting report as though he had spent the previous few hours analyzing two seasons of game tape and had not missed a day at the rink, even though he left the sport for good prior to Bryan's last season in Kingston.

Fogarty could move left, he could move right and pivot in either direction while moving backwards so well that you couldn’t see a difference. He “skated one leg at a time” and that gave him the movement which made it difficult for the opposition to establish a forecheck.

When he had the puck in his own end, he either skated it out himself or could neatly find an outlet “much like Raymond Bourque.” He had soft hands and carried the puck in a great position out in front of his body like Wayne Gretzky. With his skating ability he could take advantage of open ice and pass just as easily on his backhand as he could on his forehand.

In his short time getting to know the wunderkind, he very much liked the young man who came across as “very congenial,” — shy but outgoing once he found his element. He had the build of a lumberjack and a gravelly voice to match. A 16-year-old that sounded 35.

O’Donnell of all people is uniquely suited to speak to the Orr comparisons. He played two seasons with the Boston Bruins in the early 1970s and there is clear hesitation to go as far as to say they were similar, but that is no slight. After all, if God made man in his own image, even the closest thing could only be a replica.

Most of the greats are born with it, they seemed destined to reach the pinnacle of their sport from an early age. Bryan had that in his game.

He dazzled at the Quebec International Pee-Wee Tournament as a 12-year-old. His coach then, Brian Eadie, recalled the crowd in the Colisée applauding his rushes and passes.

“They were amazed,” he told the Brantford Expositor.

At age 15, Fogarty moved to Junior A with the Aurora Tigers, north of Toronto. Owners Ted Tobias and brothers Joel and Steve Ross had scoured high and low to assemble a team that could win the national title. Bryan was by far the youngest amongst many older players and more talented than them.

Tigers goalie Paul Cohen saw Fogarty render players four and five years older feeble in their attempts to separate him from the puck. He improvised in ways that went against the grain for what defencemen were expected to do.

“We had guys with years of OHL experience, like Jim Mayne, go after him behind the net in 2-on-2 drills. Next thing you know, he banks the puck off the net or puts it between his legs off the boards and shifts his weight, they could only get a piece of him, it was comical.”

Tom and Virginia's son was said to be severely anxious and unbeknownst to nearly everyone around him, nearly deaf in his left ear. Later it would cost him when people thought he was stuck-up or being inattentive.

As the story goes, the shy kid drank to fit in.

Social anxiety by definition is a prolonged and lasting fear of being humiliated and scrutinized in social situations. The median age of onset, in the early to mid-teens, sadly intersects precisely around the time Bryan would have been leaving home to play in Aurora.

Later in his life, he told his mom it was like being stuck on a railroad track and being unable to move.

While there are truths to the perils of leaving home at that age, there were already warning signs.

Well tenured hockey writer Ken Campbell wrote in 1999 that Fogarty had his first drink at 14. Like many kids, it started with raiding a liquor cabinet with friends and going to the high school dance.

In Aurora, he began building the reputation that followed him on and off the ice throughout his career.

“Even when he was starring in Aurora on a team that was laden with 20-year-olds, Fogarty would often show up to practice with rosy cheeks that the team thought was from tobogganing. He went through five boarding houses that season.”

Fogarty’s father Tom was said to imbibe, once even offering Bryan’s second coach in Kingston, Jacques Tremblay, a half-empty bottle during an intermission of a game at the Memorial Centre.

“Thanks for looking out for my son!”

A startled Tremblay politely refused. While walking back to the dressing room, he quickly surmised where the rest of it had gone.

When Dr. Peter Scalia was coaching adolescents in New Hampshire’s Granite State League, each January he’d invite a fellow academic, Manish K. Mishra, to warn the 13- and 14-year-olds about the dangers of substance abuse.

That did not happen much in junior hockey dressing rooms thirty-five years ago. The link between mental health and addiction is an area of medical study that has grown exponentially. It has been driven in large part to fRMI, the digital scans of the brain that show which parts light up when exposed to drugs and alcohol.

“It’s night and day,” says Mishra, who specializes in addiction psychiatry at Dartmouth College. “We know now unequivocally addiction is a disease, not a moral failing.”

Some people are so predisposed through biological, psychological and social factors. Through one or any combination of the three, they are born on third base, but getting to home means the game is over.

What’s the difference between two guys that have their first beer at 15, but by age 20, one can call it a night after his third or fourth drink while the other drives home after five more?

It doesn’t happen overnight

“It’s a slow burn,” Mishra says.

The learning curve was steep for a defenseman of that era and Bryan was able to step right into an older Kingston defence corps in 1985. He scored his first OHL goal in the Canadians’ seventh game, on Oct. 13 against the archrival Belleville Bulls.

In the second period he took a loose puck over the offensive blueline and skated unmarked through the left circle before outwaiting the charging goalie and sliding the puck into the net.

He scored his only other goal in Hamilton eight days before the holiday break. In between those two goals were the first of two team suspensions for curfew violations, the second of which gave his coach reason to pause and ponder the young man’s future.

Captain Jeff Chychrun picked up his home phone. On the other end was O’Donnell. He was considering sending Fogarty home, but the veteran recognized his importance to the team and suggested they continue to work with him.

And they did.

Fogarty swore it would never happen again

The team had reason to be hopeful. Despite their stars’ slip-ups, he finished the season with eight points over their final five regular season games for a total of two goals and 19 assists in 47 games. He represented Canada at the Esso Cup, the de facto world under-17 championship.

Kingston had a franchise record nine-game win streak over February and March before winning their first playoff round in five years.

1986-87

Jeff Sirrka was astonished at the specimen he saw arrive at training camp the following season. This was not the doughy kid he saw one year ago, Bryan had transformed into a lean machine. He was more than happy to impart a diet of champions to Sirrka, half seriously.

“He was telling me what to eat, and what I shouldn’t,” Sirrka recalls.

Fogarty’s commitment to body and mind led to his best season in Kingston. His mother, Virginia, also came to town to live with him. That was not common at the time, but it kept him in line to some degree.

A year older, he started to earn more trust on the ice and spent time on the power play. With Chychrun moving up to play pro in the Philadelphia Flyers organization, Fogarty switched his jersey number from No. 8 to 88. At the time, not many skaters had numbers above 30 and high double digit repeating numbers were the sign of stardom, like Wayne Gretzky’s No. 99 or Mario Lemieux’s No. 66. Ray Bourque was just about to go from 7 to 77.

He would switch to No. 43 in Niagara Falls, as Drulia (No. 8) and Jamie Leach (No. 88) both had tenured rights on his former jersey numbers. Pearson suspects he was assigned the number during his first NHL training camp and went with it after moving to the Thunder.

The flu kept Fogarty out of much of pre-season. On Oct. 17 the marquee outside the Memorial Centre read that the Bulls were in town. Fogey would feast on the Canadians’ archnemesis this season, starting off with a goal and two assists. On Halloween, during a 6-4 win against the Cornwall Royals, he began a 10-game point streak that carried into the final contest of November.

Fogarty wouldn’t get a chance to try to earn at least one point in all 11 games that month.

O’Donnell suspended Fogarty and 19-year-old centre Peter Viskovich for breaking curfew. Normally, that would warrant only a fine if a player was up to an hour late coming home. O’Donnell called it “a major curfew violation” and told the Whig-Standard that their absence compounded the team’s injury problems.

Entering December, Bryan was in the running to become the top-scoring defenceman in the league, his 27 points were just one point behind leader Darryl Shannon until nasal surgery and a tonsillectomy sidelined him until Dec. 30.

When he did return against the Oshawa Generals. O’Donnell was relieved to insert him into an injury filled lineup along with forwards Steve Seftel and Mike Maurice.

The Canadians hadn’t won since Fogarty’s suspension and subsequent health issues, losing eight in a row, but the streak continued as they finished the year with a 6-4 loss.

When play returned in January, so had Bryan’s nose for the net. He quickly reasserted himself as a threat with five points (1 goal, 4 assists) in the Canadians first three games

Fogarty then had his biggest outburst of the season in a 8-4 win against the Toronto Marlboros on Jan 13. He scored once and had three assists to begin a nine-game point streak. He put up 23 points in 13 games that month. In the midst of that run, he broke the 11 p.m. curfew again, along with three other teammates. They got away with fines even though he was labelled as the major violator.

“It’s something we’ll have to talk to him about and iron it out,” O’Donnell told the Whig.

Fogarty acknowledged that his dereliction was a “bad” thing to do and he was going to have to “stay out of trouble.”

Belleville and Kingston played nine times that season as both middling teams jockeyed for playoff position. The Canadians had not won in Belleville in three years. Bryan helped put that to an end as the playoff push ramped up in February. He scored the winning goal with a slapshot from the left point and got the empty-net sealer in a 5-3 win.

Pearson put up four points that night and the team blasted Bon Jovi’s Living on a Prayer and sang off key on the hour-long bus ride home down Hwy. 401 toward Kingston.

On longer trips they might be sleeping and be jostled out of their slumber when someone would yell “ALCAN!” as the glowing lights of the aluminum plant would signal their homecoming. That night, there was no need, they were buzzing.

As a 17-year-old, Fogarty led all rearguards with 70 points in 56 games, averaging 1.25 points per game. The performance put him in the running for the Max Kaminsky Trophy awarded to the most outstanding defenceman.

He had led an informal poll created by Windsor Star writer David Hall who described him as “a tower of strength for the largely disappointing Canadians.”

The numbers indicated he deserved the award but Kerry Huffman, who had split time between the Guelph Platers and the Philadelphia Flyers, took it home.

Fogarty was named a first-team all-star, and MVP by both the team and fans. The Canadians nominated him as their candidate for OHL player of the year.

By March, a few scouts had confided in sports scribe Jim Proudfoot that he could go No. 1 and NHL Central Scouting placed him as seventh overall in the 1987 pre-draft rankings amongst a class that was brimming with talented defencemen. Five of them — Glen Wesley, Luke Richardson, Stéphane Quintal, Eric Desjardins and Mathieu Schneider — would play over a 1000 games.

In the second-last game of the season, he scored twice and had an assist in a 9-2 fight-filled win over the Toronto Marlboros to clinch a playoff spot for the Canadians. His actions warranted a suspension, however, this time his coach wasn’t left to deliberate on a difficult decision.

With the game climbing out of reach for Toronto in the second period, Fogarty was the third man in as Toronto’s John Blessman pounced on Pearson.

Pearson had just returned from a broken left wrist and was still wearing a soft cast. He was a sitting duck and Fogey knew it.

He got two games for his actions.

“Fogarty was an inspiration tonight,” O’Donnell said. “He did it all. He did some things you haven’t seen in a while. Some night’s he’s worth the price of admission.”

1987-88

After being drafted in June, Fogarty had two seasons of junior eligibility left, but only one more in Kingston, and it was memorable for all the wrong reasons. Even though he continued to impress on the ice, his time there was nearing an end.

It wasn’t uncommon for a couple teenagers to cut class at Bayridge Secondary School in the developing west end of town and shoot pool before heading downtown for practice at the old arena on York Street. While seemingly everyone that age partied, when most people called it a night, Fogarty kept going.

The cracks had revealed themselves early and became most apparent in his final year in Kingston, where the structure was about to take a hit with the departure of O’Donnell.

Fogarty loved to have a good time and was the life of the party. Sometimes that led to starting early at a place like the Lakeview Manor in Portsmouth Village, where strippers would perform in the daytime and a local band such as The Tragically Hip would take the stage at night.

O’Donnell had left in the offseason. His replacement was Jacques Tremblay, who suffered humiliation on a personal and professional level in one season behind the bench.

While Fogarty’s individual records shine through a clouded career, he also bears the distinction of being a member of the 1987-88 Kingston Canadians. They set a league record with 28 consecutive losses — and that came after an 8-20 start.

Mike Cavanagh was a rookie that year. Two seasons later, when the smoke began to clear, he described the bleak atmosphere that became increasingly toxic and devoid of veteran leadership save for a few exceptions.

“Rookies like me who were supposed to look up to the older players… how could you look up to guys who wouldn’t even back you up,” he told Patrick Kennedy of the Whig Standard in December 1989. “Somebody’d get pushed around and nobody’d defend him. Pretty soon the whole team was getting pushed around. I remember it like it was yesterday.”

Fogarty missed 18 contests with a separated shoulder. He was diagnosed with bronchitis and asthma, along with severe allergies to house dust, wool and horses. That factored into his hampered play in December.

“I’m on the ice for 20 seconds and I can’t breathe out of my nose and because I’m not getting enough oxygen I’ve got no legs,” he told the Whig’s Tim Gordanier. “I feel dead. I skate up the ice and I can’t finish off the plays.”

When he wasn’t playing, he would help Tremblay, taking the ice at practices without equipment and working with the other defencemen. During games, he would join Tremblay behind the bench.

When he was playing, Bryan was Bryan, near the top of team scoring with nearly a point per game.

Prior to the season he was sent home from the national junior team evaluation camp with three other players for disciplinary reasons. It was thought to have cost him a spot in the mid-season OHL and QMJHL all-star challenge, which mirrored Rendez-vous ’87 between the Soviet Union and Team NHL. The omission was not on account of performance.

“I’ve coached in Quebec for three years, and I’ve seen all four of the previous all-star games that Ontario’s played against Quebec and if there’s one guy that can change the score in Hamilton, if it’s going to be a one- or two- goal game, it’s Fogarty on the power play and 5-on-5,” Tremblay said.

“We have to stop thinking that the only way to beat the Quebec league is to hit them. The one way to beat them is to bring the puck to them and I would say right now (Fogarty) is as good as (Mathieu) Schneider as far as that is concerned. He’s one of the best defencemen that I’ve coached in my 23 years.”

Fogarty appeared remorseful.

“I guess what happened at the junior camp hurt me,” he told the local paper. “It could be detrimental to my future in many ways.”

Darcy Cahill, a young star in his own right, joined his hometown team that year through a trade with the North Bay Centennials.

He had played briefly in Kingston during Bryan’s rookie season as a 15-year-old call-up at the end of the season, which was allowed at the time. The first time they met, Fogarty, the 16-year-old, called him “Double Underage.” It never was cut with malice but rather, it rang as a term of endearment.

“He was the most modest human being I’ve ever met,” Cahill said. “For being so good, he was so modest.”

By good, Cahill means great. What he had witnessed in training camp two seasons earlier, he now saw every time the big fella hit the ice. Fogarty had an cosmic blessing, it looked like he wasn’t even trying.

“Playing the power play with him, I’d be at the top of the right circle, he would on top (at the blueline), I’d give it to him and with one little head shake — like I’m coming at you — the whole rink would freeze, then he’d take that little half slap shot that he had and it would basically be rolling into the top corner of the net.

“It just had eyes, every play he made had eyes, because he never dropped his head.”

Off the ice, Bryan’s situation escalated.

Curfew violations and getting bounced from billet homes were one thing. A purported impaired driving charge was another, and it wasn’t long before he was part of the wholesale changes taking place in the Limestone City.

“I don’t think hockey was his number-one priority,” said Chychrun. “The skill sets were off the chart and I don’t think Bryan really ever harnessed that off the ice and capitalized on the talents he had.”

In the offseason, the original ownership conglomerate was looking to sell the team. By February, in the middle of all that tumult, came even more, when a loose cannon, former minor league hockey player turned real-estate developer was announced as the purchaser.

As Lou Kazowski watched the losses pile up, he did what any reasonable owner would do just a few weeks into buying a team. He put himself behind the bench — during the middle of a game on March 4, 1988.

Losers of 22 consecutive games and trailing 7-2 at home to the Peterborough Petes after the first period, Kazowski took matters into his own accord. He went into the dressing room and released hellfire before taking taking the helm. Jacques Tremblay resigned the next day.

“I think most of the guys were scared after the new owner came into the dressing room at the end of the first period Friday night,” Fogarty said. “The guys were upset with the way Jacques left and the way he was treated. He did a good job all year and I don’t think there was the right chemistry on this team to put together a winning team.”

He was the first person to visit Tremblay after he was fired.

Leading scorer Steve Seftel, a second-round pick of the Washington Capitals, lamented the circumstance clouding his final days in junior.

“I'm sorry to be finishing my third year this way with all this turmoil.”

As for Kazowski, he promised wholesale changes and a team that would be much tougher the following season.

Prior to the 1988-89 campaign, Kingston would adopt the name and silver-and-black colours of one of the NFL’s most popular franchises - The Raiders, with a similar logo to boot. “Real Hockey is Back in Town,” a bumper sticker proudly pronounced.

Kazowski’s reign would culminate with him almost extracting the franchise from this “bad hockey town” at seasons end. A brash allegation for a city which boasts a hockey holy triumvirate of Don Cherry, Doug Gilmour and Kirk Muller, along with Olympic gold medallist Jayna Hefford.

It was Kingston’s version of Bob Irsay relocating the Baltimore Colts to Indianapolis in 1984, moving vans and all. However, unlike that anguished tale, the franchise was saved and named the Frontenacs ahead of the following season. They have been playing OHL hockey in Kingston under that tag ever since.

The Raiders finished last in their division, while Bryan would get a new lease on hockey life on the other side of Lake Ontario.

On Aug. 18, he was traded to Hamilton, along with prospect Devon Colquhoun, for three players and two draft picks. He left Kingston as their third-highest scoring defenceman in franchise history.

Before he could even play for his new team, they became the Niagara Falls Thunder after failing to work out a lease at Copps Coliseum.

While Fogarty put up point after point, the Raiders piled up loss after loss. New Kingston coach and GM Larry Mavety cut straight to the chase in a December newspaper interview with an assessment of Bryan’s fortunes as well as that of his own team.

“Do you think Bryan Fogarty, if he had stayed here, would have 80 points at this point in the season on this hockey club?” he asked the Whig’s Claude Scilley. “He’s playing on a very good hockey club, a contender for the Memorial Cup.

“I think it’s been beneficial to Bryan Fogarty,” added Mavety, who died in 2020. “He had a reputation in this city and I just think it was better for him and everybody involved that he went to another one with a new lease on life. Basically, I think we did him a favour.”

Fogarty’s OHL was a blue collar game played by blue collar stock, sons of working people. That was also reflected in the crowd.

Men referred to derisively as N.O.P. — North of Princess — by uppity locals and bluebloods attending Queen’s University, watched from standing room, raining pink confetti on the crowd when the 50/50 draw didn’t come through.

Smoke lingered long in the concourse from intermission cigarettes well after the puck had dropped to start a new period. The alcohol permissible section, known as the Lion’s Den, was literally a blue cage under the stands where the penned-in beasts would roar, causing an unsuspecting child to drop their fries as they rounded the corner.

Bankers, doctors, lawyers and businesspeople were at Maple Leaf Gardens in the golds or occupying the seats behind the Canadiens bench at the Montreal Forum. Today, their grandsons climb the ranks of a sanitized game.

Chychrun, now an NHL TV analyst in Florida, is the father of a pro. His son Jakob is a defenceman with the Arizona Coyotes.

Jakob Chychrun was also a first overall pick in the OHL, like Fogarty. And, like Bryan, his potential led to him becoming a high NHL first-round pick in 2016.

Jeff remembers that by the time his son began playing junior for the Sarnia Sting, he was already locked in and focused on professional hockey. Jakob and his teammates were taking supplements and constantly working with trainers in the gym. They ate right to fuel their big league pursuits and school was never thrown to the wayside. Major junior hockey offers players an education package that covers university tuition if they do not stick in the pros.

The word ‘regimented’ works as a catch-all term.

“We were definitely in the dark ages back then,” Jeff says. “Now you go to a major junior hockey room, they’ve got a little kitchen and a short-order cook at times to feed the boys. Today’s kids grew up knowing what you get at the GNC store. They are insulated and driven to be professionals right from the start. Back then, I don’t think we had that vision.”

No pizza and wings after the game and certainly not as many older players dragging the young guys out on the town either.

Jeff Sirrka is a narcotics officer in Colorado, and on the odd Friday he laces them up, taking the ice with a group of western Canadians working in oil and gas. At age 53, even when he is spotting some players a few years and a little quick-burst acceleration, he is still the 12-year pro who has to dial it back and take it easy on them.

“I’m mostly there for the beers and bullshit,” he says, welcoming the camaraderie as a reprieve from the stresses of his job.

In the room after a game, the voices blend together until it gets quiet, he bends down to untie his skates. For a moment he is back in Kingston at the Memorial Centre. He looks up and sees a fellow defenceman such as Marc Lyons taping his stick, tough guy Marc Laforge putting on his shoulder pads, and Bryan off in the corner, grinning. The din of chatter returns, and he blinks back to reality, where he is among middle-aged sales reps and site managers.

“A lot of times in Kingston it felt like we were all we had.”

On a late summer day at his cottage west of Ottawa, Chychrun sits on his dock as the wind barrels in over the lake, and he processes his thoughts of the one season he spent with Fogey.

He was only 19. Still though, he wishes he had the life experience and wherewithal to do whatever he could to help Bryan. Perhaps wake him up in the morning or even more, put his arm around him, talk and listen, whatever it might have taken to help the kid along.

“He had it all, he could shoot a puck, make room for himself, I think he had every tool in the box natural talent-wise,“ Chychrun says. “You look back though eh, and go, ‘what if?’ ”

“Being born is going blind, and buying down a thousand times

To echoes strung on pure temptation”

- Nothin – Townes Van Zandt.

Aug. 8, 1992

There is a flame running through John Kordic’s veins as he readies for another fight, but tonight it won’t be adrenalin that has his heart racing and his eyes as wide as saucers.

In 87 career scraps, his dance partners often had no chance. Tonight, that fate awaits him at Motel Maxim in the Quebec City suburb of L’Ancienne-Lorette.

He is used to hearing his name on sportscasts or on Hockey Night in Canada. You can’t spend six seasons playing for the Montreal Canadiens and Toronto Maple Leafs and not feel like you are in a fishbowl, especially if you are considered one of the league's heavyweights.

This Saturday will be different. Kordic will be dead by midnight.

The manager called the police to report a hulking freighter of a man being disorderly, probably drunk, harassing staff and guests. The first officers to arrive have called for backup and now more than half-a-dozen have managed to wrangle the behemoth down to the floor and pin him. Two sets of handcuffs are used to restrain his arms and his legs are also bound.

Bruised and bloodied, Kordic loses consciousness in the ambulance and dies en route to the Laval University hospital.

Back in his room, police find a box with 42 syringes. Beside the bed in a blue duffle bag emblazoned with the Nordiques logo, are three more. They contain traces of cocaine and an illegal steroid.

Two months later at an inquest, Dr. Georges Miller said he had never seen cocaine levels that high in the 20 years he had been practising as a pathologist. He also testified that the autopsy showed needle marks in Kordic’s muscle tissue and an enlarged heart and liver which was consistent with steroid abuse.

Kordic's death was the result of his large cocaine consumption, Miller said. Even if he hadn't fought the police officers, he would have overdosed. Kordic was reported to have met his end as the result of a pulmonary edema following heart failure.

At his funeral, Kordic’s family lamented the loss of a son and brother.

It was a wake-up call that his former roommate with the Nordiques did not ignore.

“It opened my eyes,” Fogarty recalled three months later. “When you know someone that close with the same kind of problems — it showed what can happen.”

He was now skating with the Pittsburgh Penguins, a fresh start that hopefully would turn out better than it did in Quebec.

A franchise which was unstable from the top down.

1989-90

An emergency appendectomy delayed Bryan’s NHL debut by a month. He needed a conditioning stint with the AHL’s Halifax Citadels before he was ready to be thrust in to the spotlight once again.

Prior to his first game on Nov. 8, 1989, he addressed the Orr comparisons. “There is no possible way you can compare me to Bobby Orr,” he said. “He has had an illustrious NHL career and I haven’t played a game yet.”

Bryan, much like he had in Kingston, joined a team in Quebec that was mired in failure and flighty management.

The Nordiques had missed the playoffs in the previous two seasons, at a time when 16 of 21 NHL teams reached the postseason. Entering play against the New Jersey Devils, the team had lost seven games in a row and were 3-11-1 on the season, the worst record in the NHL.

Injured star forward Michel Goulet was delicate in his assessment of what he had seen, explaining that when a few players were out of the lineup or slumping the team folded but there was talent bursting at the seams.

“When we have everything going for us, we can rival anybody,” he said. “But right now, we’re fragile, very fragile.”

It was the same story against the Devils. They were tied before giving up two goals to close out the second period. They lost 6-3, their eighth in a row.

Jean Perron, who had spent the previous season as interim coach, now opined on talk radio station CJRP-FM that the team was like “a dead horse” and could be out of the playoffs by Christmas.

Bryan was born in Montreal and was raised in the suburb of Dorval until he was nine and naturally had gravitated toward the powerhouse Canadiens of the late 1970s. What a thrill it would be to face the Habs for the first time in a home-and-home series at the end of November. Although the Nordiques lost both games, Fogarty scored his first NHL goal on a breakaway during the second game at Le Colisée, leaping out of the penalty box right on cue for a pass from Joe Cirella. Chris Chelios bore down but couldn’t close the gap.

“By the time he saw me, it was too late,” Fogarty told the Montreal Gazette.

As Goulet alluded to, the team was talented but listless. Amongst the stars was 20-year-old Sakic who thrived at centre and would wear the captain’s ‘C’ when veteran Peter Stastny was out of the lineup.

Joe and Bryan were the Nordiques’ two first-round picks in the 1987 NHL draft. They were born less than a month apart in 1969. Sakic preceded Fogarty as the Canadian junior player of the year with the Swift Current Broncos in 1987-88.

Sakic had the benefit of an easier transition to the pro game at forward. As a rookie defenceman on the most porous team in the NHL, Fogarty shouldered criticisms that weren’t his alone to bear.

“Joe’s been doing his part with lots of points (38),” Fogarty said. “Younger guys like myself make many mistakes - that’s expected - and the older guys have been taking most of the blame.”

The Nordiques bottomed out at 12-61-7, one of the worst records in league history, which placed them alongside overmatched expansion teams that have set high-marks for single-season futility. Quebec was in their 11th NHL season.

Midway through the next season, Michael Farber wrote that Sakic regularly starred “on a team where the only other constant has been chaos” and never allowed “his game to sink to the level around him.”

Cited in particular was the Eric Lindros soap opera and the push by owner Marcel Aubut for the city to build a new arena to replace the 40-year-old Colisée. The Nordiques had also burned through several coaches and GMs since Sakic’s first training camp in 1987.

“The sideshows almost seem to overwhelm the main event,” the Montreal Gazette reporter wrote in December 1990.

Sakic’s draft classmate was in the same boat and tied to a team in turmoil yet again. He also had NHL contract money to sprinkle around in an exciting big-league town where the blueline could give way to white lines.

1990-91

The next season started off well enough for Bryan. He had four points in the Nordiques’ first three games, and a career-high three assists against Detroit on Oct. 13. It preceded the start of a franchise-record 17-game winless streak.

During a brief reprieve, Fogarty netted the Nordiques’ first NHL hat trick by a defenceman in Buffalo on Dec. 1.

He scored two in the second period to break a 1-1 tie. The first was that heavy slapper through a Tony McKegney screen from the left circle. Thirty-five seconds later, he came in from the point and was set up in front of the net by Stéphane Morin. He netted his hat trick with another blast that squeezed through Clint Malarchuk’s pads

In the dressing room, Fogarty had a laugh with the cluster of reporters after a self-effacing comment. He attributed his good fortune to a new pair of skates. He made the same joke later that night when he called his last junior coach.

“No Bryan,” LaForge said on their phone call later that night. “You’re just really good.”

His performance even elicited a seldom seen smile from head coach Dave Chambers, who complimented the 21-year-old on not only his offensive outburst, but for being responsible in his own end.

With a tie the next night against Calgary, there was a slight break in the storm. Quebec had gone four games without a loss, something they would only do twice during a season where they won just 16 of 80 games.

So for now, relief, but it was about to get worse and the look on Chambers’ face would be the farthest thing from a grin.

Each loss exacerbated the talk of losing for Lindros. The Big E was the next big thing, a hulking centre for the Oshawa Generals with skills and a mean streak. The Ontario Hockey League created a rule to allow for first-round draft choices to be traded after Lindros refused to join the Sault Ste. Marie Greyhounds. He and his parents had similar expectations about his agency with deciding where he would take his talents in the NHL.

Fogarty was progressing on the ice while playing on a cellar-dweller for the third time in four seasons, going back to his last year with the Canadians.

He responded in the media by relating his experiences in that third dreadful season in Kingston.

“We’re young guys and we know we’re going to have a tough time adjusting,” Fogarty told the Globe and Mail. “But we know there’s going to be a bright side someday.”

Fogarty had 20 points in his first 25 games, easily topping the 14 he had as a rookie. He led the team’s defencemen in points despite playing only 45 of the 80 games. Plus/minus was the stat used to sum up all-around play. In spite of the losing situation, he had improved to minus-11 after being minus-47 the season prior.

Quebec’s young nucleus included Sakic, Mats Sundin, Owen Nolan and Curtis Leschyshyn. Former Red Wings coach Jacques Demers, who was working as an analyst on Nordiques broadcasts, described Bryan as the linchpin in Quebec’s rebuilding.

“Fogarty has turned out to be the quarterback they need on defence,” he told Jim Matheson of the Edmonton Journal. “The thing you need in the league to be successful.”

John Muckler, who had coached the Edmonton Oilers to the Stanley Cup the previous season, said there were parallels to the Oilers of about a decade earlier.

“They have many young players that a lot of teams in the NHL would like to get their hands on,” he said. “You have to be patient with them because they’ll play poorly one night and very good the next.

“You just don't know what's going to happen on any particular night.”

Leschyshyn was born the same year as Fogarty and Sakic. His late-September birthday put him in the 1988 draft cohort and the Nordiques invested their No. 3 overall choice on him.

He is now a pro scout for the Colorado Avalanche and observed Fogarty up close when he was the same age as current Avalanche standout Cale Makar, the offensive defenceman who was the NHL’s rookie of the year and a Norris Trophy finalist during his first two full seasons.

“The comparison is fair,” he says. “That’s their style, to slither and move in and out of traffic with the puck. (Though) Bryan was six-foot-one, six-foot-two — back in those days, big men didn’t move that well, he was an anomaly. There were only one or two or three guys throughout the league that could play like that and he didn’t play a lot of those games at 100 per cent. He was limited because of the way he lived off the ice. What he had was God-given.”

For Bryan, the offensive part of the game was intuitive but his defensive play was maligned. Fogarty could be prone to giveaways when put under pressure. The charge had followed him from junior.

Cahill felt it was a little heavy-handed, because of how much Bryan tended to have the puck.

Chambers felt he had taken a step toward becoming the total package and was playing with confidence.

“It helps to go both ways,” Fogarty told the Calgary Herald. “You can’t just rely on one way to get you through the year. I had a tough year last year but it's been a lot easier this year. I’m really happy with the way I’m playing right now and how the team is going.”

In November, Fogey’s old pal from OHL re-entered the picture. The Nordiques shipped out three veterans to the Toronto Maple Leafs for Scott Pearson and draft picks.

GM Pierre Page had taken heat for dealing veterans Aaron Broten, Lucien DeBlois and Michel Petit. It was read as part of the push to tank so the Nordiques would finish dead last and earn the right to draft Lindros with the first overall pick in the 1991 draft.

Page begged to differ, and as part of his rebuttal, cited Petit’s departure as a chance for Fogarty to see more ice. How could he be deliberately taking a nosedive when he was giving his blue-chip sophomore fertile ground to blossom?

Fogarty tapped in his sense to anticipate when the stakes were raised. He helped the Nordiques earn three-of-four possible points during a home-and-home with the Canadiens in late December. Fogarty’s goal in the first game started a comeback, and he had the primary assist on the Nordiques’ goal in a 1-1 tie in the second contest.

“Joe Sakic is our leader and the guys accept that,” Nordiques goalie Ron Tugnutt told the Vancouver Sun. “He and guys like Bryan Fogarty are the guys we expect special things from and the rest of us just have to do our jobs.”

The promise was put in writing with a contract extension in late December, but all the encouraging signs on the ice were short lived. Everything with Bryan seemed that way.

Bryan not only had three coaches in as many seasons with the Nordiques, but he had three very different coaches. His first was fiery Michel Bergeron, who came by his nickname of Le Petit Tigre honestly. Bergeron was replaced by Chambers, a cerebral tactician who was everything Bergeron was not.

Bergeron shot from the hip. Chambers was a quiet scholar. The 50-year-old had only been in the NHL for a season, as an assistant coach in Minnesota. He had been hugely successful within Canadian university hockey at York University in Toronto where he was a member of the faculty, but that did not cut any ice with NHL players.

Commanding respect would be a challenge.

It didn’t help that his most skilled offensive defenseman who had all the right moves stirred up gossip with his finesse off the ice.

There were reports he had exchanged phone numbers with Chambers’ daughter in a bar. A later story in the Globe and Mail stated Fogarty had invited her and her friends to his apartment. He found out who her father was when she called home for a ride — at 3 a.m.

The story broke during a three-day break between games in January and with it, Fogarty’s momentum seemed to leave him. He was a combined minus-five over two games against the Maple Leafs and Devils on Jan 22 and 24. Then he disappeared.

Was he working on his tan? Could he be looking into real estate? Maybe he was in Florida? Where on God’s green earth was Bryan Fogarty, because he sure wasn’t in Halifax.

Forty-eight hours after the 6-1 defeat against the Devils, he was demoted to the Citadels in the AHL. That was announced on Saturday, by Thursday, word traveled that he was missing in action.

As it appeared, the team and the player were both fine with keeping things under wraps. By Feb. 2, a week after he was said to have been assigned to the minors, it was becoming apparent that the whole thing was a ruse.

His agent, Gus Badali, confirmed Fogarty was getting help, Citadels spokesperson Bob Cole said, “I don’t think we’ll be seeing him for a while.”

Quebec media liaison Jacques Martineau stated that the team hoped he would “report as soon as possible.” When pressed, he acknowledged Fogarty was not under a deadline to report and had not been suspended.

“He is consulting the people he has to consult to make the decision on whether or not to report to the Citadels,” Martineau told the Globe and Mail. “We want to give him time.

“It’s not up to us to decide what he will do.”

If the flacks would not come right out and say it, then Thomas Fogarty would. “His head is really screwed up,” he said while playing coy as to his son’s whereabouts. “He has a few personal problems.”

Then the stark reality of the situation came to the forefront.

Page told The Canadian Press that Fogarty was alcoholic and would need three months of treatment. He would attend 90 meetings over that time.

“Normally, that many treatments is the key to success.”

But one month at Spofford Hall in Chesterfield, N.H., appeared to be all that he needed. Their power play had slipped from 11th to last in the league without their daring QB.

Page and Offenberger traveled to the Maritimes ahead of Fogarty’s return.

Offenberger gave details on what had transpired in early February, telling the Edmonton Journal’s Jim Matheson that Fogarty had approached him about his drinking.

One episode that stood out was the time he and teammate Darin Kimble spent the better part of a Sunday afternoon watching football in Old Quebec. When they left, Fogey took the keys to the rugged forward’s Jeep.

After stopping for gas near their apartment complex, they were rear-ended pulling back out onto the road. Fogey jumped out and tried to run for it, but was soon waist-deep in a snowbank. He didn’t have a driver’s licence.

Fogarty’s problems were accelerated by non-hockey friends that acted as enablers.

“I can’t think of anyone who would have had a bad thing to say about Bryan. He wanted to be everyone’s friend, he wanted to fit in everywhere,” Pearson said. “(When you get to the NHL), now everyone’s wanting to be your friend. Sometimes unfortunately Bryan may not have chosen the right people to be around in order to protect him and protect what he could become, they can bring you down. Where’s the next party and you're the big shot and we want to hang with you. A lot of people don’t recognize that before it’s too late.”

He entered rehab, where his parents and girlfriend visited him.

Fogarty finally admitted he had a problem, he said he hadn’t gone four days without a drink since he was 17.

“I asked him how good he was,” Dr. Max Offenberger said. “He told me he wasn’t sure.”

Clear-headed and upbeat, Bryan tried to skate off the rust. During his first practice with Halifax, he could tell he had been away from the game for an extended period of time.

Two days later, he was named the third star of the game.

After nearly two months away from the Nordiques, Fogarty rejoined them against the Edmonton Oilers on March 19. There were rumours that Oilers GM Glen Sather was interested in acquiring the defenceman who had been compared with Paul Coffey, a guy he’d had to trade to Pittsburgh a few years earlier.

The Nords lost again, 7-6 in overtime, Sakic dazzled his home crowd with a hat trick and two assists as he hit the 100-point plateau for the second consecutive season.

The Oilers rumour persisted throughout Bryan’s time in Quebec. Once, perhaps out of frustration, Fogarty said that he had spent time in Edmonton and it “bored him silly.”

That might shut them up.

Another lost season. Fogarty played four games, netting an assist on the road in Hartford and Boston before being shut down for the remaining six games and sent to continue his rehab in Minnesota.

Sakic, a co-captain along with Steve Finn, just wanted him to get better.

“Hockey and how much he can help the team never enters my thinking on Bryan,” Sakic said after the season mercifully ended. “The human factor is all that matters, that a very good guy handles his problems and gets his life back on track.”

Aubut declined to sign a five-year lease with the city to remain in Le Colisée, then in June the Nordiques drafted Lindros even though he had stated he would not report to the team.

The lives of Kordic and Fogarty would intersect in Minneapolis where both were treated by Dr. James Fearing, “America’s Crisis Doctor'' of the Hazelden Foundation.

Kordic was living in a group home for recovering alcoholics. Fogarty had made a temporary off-season move to the area to be close to the good doctor, who suggested the two hockey players room together in Bryan’s apartment.

When Page signed Kordic, the motion was carried and that is how their living arrangement in Quebec was said to have been born.

In Fogarty’s Sainte- Foy flat, they filled their free time playing video games and drinking soft-drinks. As a condition of employment, they were both expected to have regular blood and urine testing, starting on Aug. 20. As it was reported, Kordic, the tough guy, would be released if he had any alcohol in his system. For Fogarty, the defenceman with power-play savvy, the consequences would be a demotion to Halifax and a corresponding drop in salary from the $250,000 (CAD) that he stood to earn with the Nordiques.

The two attended Alcoholics Anonymous meetings together. Fogarty was optimistic but said he couldn’t promise anything.

“I’ve always thought that the main thing for me is that I left home at 15 to play junior Tier II hockey,” he told David Johnston of the Montreal Gazette in a preseason feature. “A lot of the other guys were 20. We’d always go out to bars after the games. And I liked it. And with alcoholism being a disease, it just kept progressing with me.”

He opened up even more with William Houston. He said there had been times when he would be on the bench but his mind would be on where he could go after the game in search of the coldest beer and fastest women.

“That’s what I thought hockey was all about, girls and booze,” he said. “I don’t blame them for what happened to me. I was more than happy to go with them. I loved it. But eventually it progressed to the point where I couldn’t handle it anymore.”

For now he had it at bay, save for a European vacation bender over the summer. He realized then that he was falling back into his old patterns.

1991-92

On the eve of another new season, they were the odd couple. Kordic was messy; Fogey was neat. John had an edge and Bryan was easygoing. Bryan’s problems, by and large, were subtle and didn’t affect the dressing room. John could be outwardly destructive. John's voiced ruminations could be unsettling enough for Fogey to call Offenberger out of concern.

Getting through a day and sometimes even an hour was taxing on the roommates. It was a routine of Diet Pepsi, baseball on Nintendo and dreams of million-dollar salaries. If they played by the rules.

Pearson lived with Adam Foote in the same complex. He remembers walking upstairs to see Fogarty trying to walk a line that got narrower every day.

“As you go up the ladder, there are more little deficiencies that can be exposed.” said Pearson of playing the game at its highest level. “If you make one mistake and 10 great plays a coach will say, ‘I’ll deal with that.’ But if your off-ice behaviour is a knock against you, things can be nitpicked.”

The papers referred to Kordic and Fogarty as the Booze Brothers. Demers observed that every team had similar issues with players, but some hid it better.

It started off well enough. Fogarty was helping the power play get into gear, while Kordic was using his fists to hold opponents accountable.

In the first month of the season, Fogarty assisted on five of Quebec’s eight power-play goals. Kordic engaged with enforcers such as Jim McKenzie, Dave Brown and Mike Hartman.

Kordic even received a message from an off-ice official after they fought in the first game of the season saying that McKenzie admired him and wished him all the best.

The Nordiques were still not getting it done. They were 2-9-1 by the end of October. Seven of the losses were by a difference of two goals or less. But a loss is a loss and consequences come to bear in a results based business.